Remembering a True American Hero–John Glenn

They say you should never meet your heroes because you’ll be disappointed, but that certainly was not the case with John Glenn. In 2002, I worked closely with Senator Glenn on a glaucoma public service announcement campaign for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. A lot of celebrity spokespeople are happy to read whatever script you give them. John Glenn wanted to approve every last word, comma, dot every “I” and cross every “T.” It was probably the kind of attention to the checklist and detail that made him a great pilot and eventually the first American to orbit earth in 1962.

They say you should never meet your heroes because you’ll be disappointed, but that certainly was not the case with John Glenn. In 2002, I worked closely with Senator Glenn on a glaucoma public service announcement campaign for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. A lot of celebrity spokespeople are happy to read whatever script you give them. John Glenn wanted to approve every last word, comma, dot every “I” and cross every “T.” It was probably the kind of attention to the checklist and detail that made him a great pilot and eventually the first American to orbit earth in 1962.

I was very sad to hear he had passed away at the age of 95, but he lived an incredibly full life and served his country in every way imaginable, in war, in peace, in government—and of course in space.

One of the recurring themes of my career has been my luck in pairing celebrities with the right cause. I worked with Lance Armstrong before he was famous (soon to be infamous), Christopher Reeve—and many others, but Glenn was particularly memorable. Glenn had been diagnosed with glaucoma and successfully treated before his last, historic trip into space, aboard the shuttle Discovery in 1998, at the age of 77. Back when Glenn was a pilot and astronaut, you had to have perfect vision—so something like glaucoma the “sneak thief of sight” might have been especially devastating for him.

It’s harder for me to imagine a bigger American hero than John Glenn. He also defined the word “authentic.” As it turned out Senator Glenn wanted to have control of every aspect of the PSA because he was putting his name on it. He re-wrote the script we submitted several times.

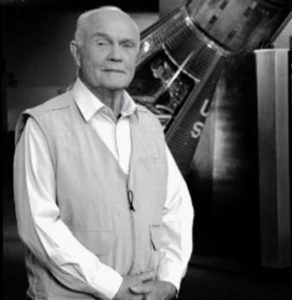

In fact, he got so involved, I decided to ask him for even more help. I had previously requested that we shoot the spot at the Smithsonian in front of his Friendship 7 space capsule. My request was denied. When I got the Senator to make the call, suddenly the Smithsonian was all ours after hours and we could even shoot in places where the cameras were not usually allowed.

At any rate, as we finally got ready for the shoot, Senator Glenn pulled out a handwritten piece of paper. He had stayed up the night before, meticulously rewriting our script again. It opened with “Close your eyes—imagine a world without vision…” He read it in a dramatic voice. I quickly realized it was a terrible idea for a TV spot—in the visual medium we want the audience to keep their eyes open. But thinking quickly, I realized how well that would work for our radio campaign. I tossed our radio scripts aside and said “Senator, we’ll use your version for radio—it’s great!” That made him happy, and allowed me to shoot the TV script as we had carefully planned and blocked out all the shots in front of his Mercury space craft.

One of the highlights of my life was having Senator Glenn give me an impromptu tour of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum when we wrapped for the night. While Glenn had said being the first American in space had been “the best day of his life”—spending a day with him was one of the best days of mine. They don’t make them like John Glenn any more. He will be missed.

Comments are closed.